AT THE CUSP BETWEEN POST-CIVIL WAR RECONSTRUCTION AND THE EARLY STRUGGLE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS: THE ATLANTA NEGRO BUILDING AT THE COTTON STATES AND INTERNATIONAL EXPOSITION

Annabella Jean-Laurent

Like the conflicting official and unofficial representations of black identity that conveyed industriousness and servitude circulating around the Piedmont Park fairgrounds, alternative, more radical ideas about black history and progress, the willingness to confront the growing anti-black racism and segregation, also circulated around the Negro Building and Atlanta. 1

Mabel O. Wilson, Negro Building: Black Americans in the World of Fairs and Museums

"A negro with chains broken but not off," by artist w.c hill. sculpture inside the atlanta negro building

The day following his famous “Atlanta Compromise,” speech at the 1895 Cotton States and International Exposition, Booker T. Washington recalled the overwhelming response he received while walking through the city of Atlanta: “As soon as I was recognized, I was surprised to find myself pointed out and surrounded by a crowd of men who wished to shake hands with me.”2 The former slave turned educator was so flustered by his sudden popularity that he shortened his visit, returned to his hotel and left Atlanta the next morning.

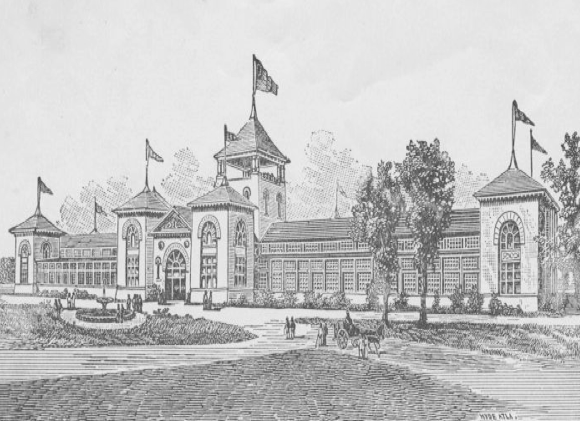

Negro Building at the Cotton States and International Exposition – October 1895

Most people in the days following, black and white, northerners and southerners, believed Washington’s speech, had resolved the so-called “Negro problem,” with his pragmatic statement: “separate as the fingers but one as the hand in all things.”3 This was proof that the New South was a progressive region free from slavery and oppression. Even W.E.B Dubois praised Washington soon after the speech, saying “Let me heartily congratulate you on your phenomenal success in Atlanta.”4 Eight months after the close of Washington’s speech, the U.S Supreme Court legitimized his “separate but equal,” stance in Plessy v. Ferguson.

Generations before Rosa Parks kept her seat, before Bloody Sunday on the Edmund Pettus Bridge, and before the sit-ins and hoses and the long march to Washington, Atlanta sat at the cusp between post-Civil War Reconstruction and the early struggle for civil rights. Atlanta’s Negro Building at the Cotton States and International Exposition was the turning point. Just thirty years following Emancipation, former slaves and free blacks showcased their accomplishments, in a 25,000 square foot building, for the first time to local, national and international audiences.

The Atlanta Negro Building, and its widely praised exhibition, speeches and many conferences created the legitimate vision for a New South, in opposition to the other widely promoted New South of the same time, whose vision was built on continued, but carefully disguised, white supremacy. The events inside the Negro Building both reinforced and contradicted Washington’s speech and formed the still-continuing debates, among African Americans themselves, about racial identity and civil rights in the political, social and cultural future of America. The significance of the Negro Building is unknown to all except those who happen upon archived photographs about the Cotton States Exposition, two scholarly books or the long history of civil rights struggles in America. Although it spawned a series of other Negro Buildings at expositions and fairs in the early 20th Century,5 the first Negro Building is a distant memory in Atlanta and America.

No one seems to remember the exact location,6 but its presence was commanding. The building, with 25,000 square feet of exhibition space, sat on the right as visitors passed through the gate from Jackson Street, now Charles Allen Drive, into what today is Piedmont Park, Atlanta’s most treasured public space. Like most of the Exposition buildings designed by Bradford Gilbert, a white New York architect who was well known as the architect of Atlanta’s Union Station, the Negro Building was built as a temporary structure, used solely for the fair and stood for just three months. It was built by black contractors, J.T. King of LaGrange and J.W. Smith of Atlanta, with entirely black labor, secured with a low bid of $9923. The Official Catalogue of the Cotton States and International Exposition described the gray shingled, Romanesque style building as a “…beautiful main front with large windows, and four corner pavilions; a large central tower rises 70 feet above the floor line, adding much to the general design. The pediment over the main entrance is artistically decorated with beautiful figures and groups representative of the life, character and work of the Negro Race.”7

But Washington’s “Atlanta Compromise” speech overshadowed the Negro Building. During the Exposition’s centennial celebration in 1895, the focus was on his speech, with no mention of the significance or even the existence of the Negro Building. Aside from a historical marker placed at the location of Washington’s speech, with only the mention of a Negro Building, no marker recognizes it or its historic site.8 Yet, the $200,000 federal funding for the Exposition was conditioned on its construction. Without the Negro Building, the Exposition might not have happened at all, and Atlanta may have had ongoing struggles to become capital of the New South.

Exhibition Inside the Negro Building

The exhibits and debates, in and around the Negro Building, as well as in the local and national press, solidified what Mabel O. Wilson, author of the most comprehensive study of African-Americans at world fairs and exhibitions, calls a black counterpublic sphere.9 Black Americans, marginalized from the dominant white culture since they first arrived on U.S. soil in the English colony of Jamestown, and since then, subject to slavery, oppression and segregation, were already forming their own public sphere. But, it is this maturing black counterpublic, resisting the dominant white culture, which began the legitimate vision for a New South and the struggle for full civil rights.

Contrary to most perceptions, African-Americans were already protesting for political change in the South, long before the 1950’s and 1960s. As early as 1881, a washerwoman’s strike in Atlanta involved 3000 mostly black cleaning women, where a labor organization was formed to petition for better wages and equal representation. This organization was later named the Washing Society.10 In Atlanta, this emerging black counterpublic was woven from the early strikes, the new black colleges, black intellectual elites, and successful black businesses, just as the Cotton States Exposition was being imagined by the proponents of the New South.

THE NEW SOUTH

Henry Grady and the New South

The New South movement emerged after the Civil War. This new class of southern capitalists, entrepreneurs and industrialists, especially the newspaper editors in major Southern cities, supported the informal movement. Henry Grady, the Atlanta Constitution editor, promoted the term in a speech to the New England Society in New York City in 1886, where he put forth his vision for a New South that would transform the region from the ruins of the Civil War to technologically advanced states ready to do business with the world.11 Grady admitted that the old South “rested everything on slavery” but argued that the New South was a “perfect democracy” that came with “new conditions, adjustments, ideas and aspirations.” Grady claimed that blacks had the “fullest protections of our laws and that relations between blacks and whites” was “close and cordial.” But in a speech in Dallas, Texas, two years later, Grady said, “the supremacy of the white race of the South must be maintained forever, and the domination of the Negro race resisted at all points and at all hazards, because the white race is the superior race….”12 This New South, which Grady and others were promoting, purposely presented a false image of racial equality to the world.

Jim Crow Drinking Fountain Laws

False, because despite the end of slavery, racial oppression and violence still existed for the eight million African-Americans living in the South. Jim Crow ruled since the election of 1876, when Reconstruction ended” and federal troops were withdrawn from the former Confederate states. Named after a minstrel act, Jim Crow was a systematic social and political set of laws and codes that justified racial discrimination and violence against African-Americans. These Jim Crow laws and parallel Black Codes “defined all individuals with one-eighth or more African blood subject to special provisions in the law” and legally barred blacks from their right to vote, marry interracially, and even serve on a jury.13 The convict leasing system, which sentenced blacks to harsher prison sentences for minor offences, operated to supply forced labor to southern landowners and businesses. Such codes and laws were part of an era that scholars have labeled “neo-slavery,”14 where African-American men and women were forced to live in extreme poverty, working for almost nothing, often to repay frivolous debts.

Nonetheless, the New South promoters continued to proclaim racial unity as solution to the so-called “Negro problem,” which was understood to be the poor conditions of the newly freed African-Americans and the South’s troubled, and often violent, race relations. It was this “Negro problem,” that James Baldwin, the African American writer, later exposed as twisted and riddled with racist intent. “Baldwin… redefines the “Negro problem,” as a problem of white America.”15 The the so-called Negro problem is not a black problem, but a white one, that resulted from the systematic rule of racism that governed American society.

Long before Baldwin’s essay, Carl Schurz, a Missouri state senator, reported his findings on the state of Southern black life just three months after the Civil War. He argued that the “reactionist,” or pro-slavery supporter, those who “fiercely insist that the South must be let alone,” was at the center of the race problem. Schurz concluded, “There will be a movement either in the direction of reducing the Negro to a permanent condition of serfdom -- the condition of the mere plantation hand, alongside of the mule, practically without any rights of citizenship, or a movement in the direction of recognizing him as a citizen in the true sense of the term.”16 For Schurz, the “Negro problem,” clearly rested with those fighting to uphold white supremacy.

THE NEW SOUTH AND THE NEGRO BUILDING

As the New South movement advanced, the idea of a Negro Building made sense when a group of African Americans introduced the idea to prominent Atlanta businessman Samuel Inman. The region needed to revamp its image to be racially unified. The New South organizers also wanted to avoid the mistakes made at the famous 1893 Chicago Columbian Exposition, where African-American exhibits were few because the organizers hoped to discourage black attendance. African Americans viewed much of the Chicago World Fair as patronizing and demeaning. Anti-lynching activist Ida B. Wells even felt compelled to publish a journal essay titled, “The Reason Why The Colored American is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition” 17 that year. From Chicago’s stringent screening process for all the black exhibits to racist cartoons in such publications as Harper’s Weekly, the Atlanta Exposition organizers knew it was best to avoid any obvious racial tension.18

Cotton States and International Exposition Plan- The Negro Building is in the Lower Right Corner between Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show and Midway Heights

In March 1894, black delegates, including Bishop Wesley J. Gaines, who helped found Morris Brown College, approached the Exposition organizers in hopes that they would seriously consider an equal black presence at the Atlanta Exposition. A month later, Gaines, alongside Booker T. Washington and Bishop Abraham Grant of Texas, joined the Exposition Committee in Washington, D.C. to appear before the Appropriations Committee of the U.S. Congress. It was the three black delegates’ speeches, which convinced the Congressional Committee that an Atlanta Exposition was needed. Bishop Gaines reminded the Committee of the Chicago Fair’s blatant disregard for the black community, and argued that the welcome inclusion of blacks in the Atlanta Exposition would help build better race relations, while allowing blacks the opportunity to showcase their achievements since emancipation.19

The Appropriations Committee’s black representative, George W. Murray of South Carolina, supported the bill to grant $200,000 of Federal funds for the Cotton States Exposition because it would give “the Colored people… an opportunity to exhibit the progress they have made within the past thirty years.” The Committee approved the bill, but only if the Exposition reserved a building for its black participants with free admission and space to the African-American exhibitors. The U.S. Congress agreed with a vote of 171-49.20 The first Negro building was born.

Even before the Negro Building opened its doors, the debates began. Although the Exposition’s white organizers fully supported the showcase of post-Emancipation black progress, many in the black community were opposed, distrustful of the organizers, or fearful that the exhibition might reflect badly on the community. The New South agenda was clear: the region was ready to form new partnerships with northern and international capitalists in order to develop a bigger and better economy. But because the New South would continue to rule on the basis of white supremacy, many African-Americans were rightfully skeptical of the Negro Building and its message. Some saw it as a mockery or suspected its ulterior motives. Newspapers discouraged participation for fear of racism- such as what occurred in Chicago. The Watchman, a religious journal wrote, “must we gape and wonder at cotton raised or spun by Negroes?”21 asking why such pomp and circumstance was necessary to witness black achievement. Even the appointment of respected black civic leader, I. Garland Penn, as the building’s commissioner did not ease tension. Nonetheless, on September 18, 1895 - the Cotton States and International Exposition opened its gates. The Negro Building opened with its own celebration on October 31st.

THE COTTON STATES EXPOSITION

This 100-day Cotton and International Exposition featured 12 large buildings and an additional 20 smaller buildings, some 6000 exhibits, and numerous attractions, displays, collections and performances. These aimed to promote Southern achievement in areas such as agriculture, manufacturing, transportation, and electricity. The Government Building was where the Smithsonian Institution and Office of Indian Affairs housed cultural exhibits, while the Fine Arts building displayed paintings and sculptures by Southern white artists. The Cotton States Exposition also included a Woman’s Building, the second one at an American exposition, following the first in Chicago. The highly publicized event attracted almost a million people to 250,000 square feet of exhibit spaces built on the former grounds of the exclusive Piedmont Driving Club, now the City of Atlanta’s Piedmont Park.22

Along the Cotton States’ Midway, copied from Chicago’s famous Midway Plaisance, west of the Negro Building and parallel to what is now 10th Street, fairgoers could visit cultural exhibits such as the Streets of Cairo, the Mexican Village and even the Old Plantation where minstrel-style performances romanticized the days of slavery. In one exhibit called the Dahomey Village, what was meant to be a cultural learning experience, featuring the people of Benin, had a sign outside that read “Dahomey Village: 40 Cannibals and 15 Amazon Warriors.” These venues often ridiculed and exploited those of other ethnic backgrounds, which only helped to maintain racist notions of nonwhites,” being primitive and uncivilized.23

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show, located east of the Negro Building, also along 10th Street, was one of the most popular ethnic exhibits at the fair. A traveling show that once performed for the Queen of England featured 62 Native Americans inside a 22-acre tent space that also included “cowboys and American Negroes.” Gun shows and stylized fights occurred during each show.24

SEPARATE BUT EQUAL?

Whether or not to have a separate Negro Building, instead of an exhibition in the U.S. Government Building, was also a debate among many in the black community. At the 1885 New Orleans’ World Cotton Exposition, a Colored Department was included in the main exhibition hall, which Bishop Henry Turner found especially pleasing. “All honor to the managers of this Exposition. I have not been snubbed since coming here,” Turner said about the New Orleans fair.25 But the Atlanta Exposition was the first fair to reserve an entire building for blacks. Some believed its exhibits should be located throughout the Exposition parallel and included with white exhibits. The People’s Advocate wrote that, “the Fair is a big fake… for Negroes have not even a dog’s show inside the exposition gates unless it is in the Negro Building.”26 But for the exposition directors, the separate Negro Building was key to solving the so-called Negro problem. John Collier, considered one of Atlanta’s founding fathers, believed “the race questions of the world will show themselves in the folk and folklore of the Exposition.”27 But not everybody agreed, even with the exhibition itself. Some black residents found the space inadequate and pointed out the segregated cars and chain gangs used for labor during the Exposition. But the committee had no choice. The final decision to build a separate building was made by the U.S. House of Representatives as a condition for federal funding of the Cotton States Exposition. No funds, no internationally approved exhibition. And without adequate funds for an international fair, it would have been unlikely for Atlanta to claim the position as “Capital of the South.”

There are no recorded debates about the location of the Negro Building within the Exposition grounds, but it was clearly intended to be separate. Most of the pavilions were arranged around the former racetrack and a lake, named Clara Meer, forming a picturesque arrangement on the rolling landscape. The main entry was at 14th Street, leading directly from Peachtree Street. The Negro Building was to the side, between the carnival-like Midway Heights and Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Although not specifically segregated by race, the Negro Building was located at the Jackson Street (now Charles Allen Drive) Entrance. Jackson Street happened to lead directly south through Atlanta’s mostly black Fourth Ward to Auburn Avenue, the emerging center of Atlanta’s black commerce. Perhaps one reason for its separation was the free entry, guaranteed in the same Congressional legislation that authorized the $200,000 federal grant and required the separate Negro Building. All other venues at the Exposition required payment of an entry fee. Whatever the reason – free entry, direct connection to Atlanta’s black neighborhoods, association with the less serious venues at the Exposition, or just following the racial divisions of the time – the Negro Building was separate. Whether or not it was equal, is still up for debate. But it was the first designated building reserved solely for African-Americans at a world fair, subsequently creating what later became known as the New Negro Movement.

THE SPEECH

Washington delivered his “Atlanta Compromise,” speech on opening day of the Exposition inside Gilbert’s Auditorium Building located on the westside of the fairgrounds facing the 14th Street entrance, not inside of the Negro Building. His speech was universally praised immediately after, including by W.E.B. Du Bois. The speech was only later labeled “The Atlanta Compromise” by Du Bois himself, who is credited with initiating the long debate of accommodation versus political demands within the civil rights movement.28

The Midway at the Cotton States and International Exposition, Atlanta, Georgia, 1895.

Washington urged his audience to develop an integrated partnership that would economically uplift the South. He also reminded the mostly white crowd that one-third of the Southern population were African-American and thus, urged them to allow blacks to educate themselves in important areas such as agriculture, manufacturing and farming in order to contribute to the Southern economy. “We shall prosper in proportion as we learn to dignify and glorify common labour and put brains and skill into the common occupations of life,” Washington said. “No race can prosper till it learns that there is as much dignity in tilling a field as in writing a poem.” He urged whites to look to blacks for support “in agriculture, mechanics, in commerce, in domestic service, and in the professions.” Washington told the audience to turn away from the influx of European immigrants,” that were entering the United States by the thousands each year. Rather whites should “cast down your bucket,” to the “eight million Negroes, who have, without strikes and labor wars, tilled your fields, cleared your forests, built your railroads and cities and helped make possible this magnificent representation of the progress of the South.”29

In parallel with his message of Southern economic progress, Washington urged blacks to remain subservient and politically inactive. Likewise, he petitioned blacks to “cast down your buckets,” and “[preserve] friendly relations with the southern white man who is their next door neighbor.” By urging the black race to submit to whites, Washington believed that African-Americans would be able to uplift themselves while not confronting the white political and social structure in the South. Thus, a practical education with no political involvement was the key to black advancement.30

It is this part of Washington’s speech that scholar W.E.B Du Bois criticized. He later argued that higher education and the denouncement of white supremacy would liberate blacks, even accusing Washington of legitimizing Jim Crow with the “separate as fingers,” rhetoric. 31 But Du Bois was arguing for the leadership of the “talented tenth” while Washington was arguing for the larger African American population in the South and the challenges they faced in the era of post-reconstruction. The feud between Washington and Du Bois carried on even after Washington’s death. While both men were for the advancement of the black race, and worked together on various occasions, it is their disagreement over how progress was to be achieved that fueled, and continues to fuel, civil rights debates.

THE EXHIBITION

When one first entered the Negro Building, two pediments that symbolized the progress of the American Negro stood at the front. One was a slave Mamie with her log cabin, rake, and basket. The other was a bas-relief of Fredrick Douglass. On his side was a sturdy stone church and pictures of literature and art. Between the two images, was a plow and mule, which suggested that black progress, was attainable through manual labor - a message supported in Washington’s speech and a dominant theme established by the Commissioners of the Negro Building.32

But on the Exposition's "Negro Day," on December 26 1895, when nearly 5000 blacks and 500 whites congregated inside to witness the day events, it was Rev. J.W.E. Bowen’s speech, “An Appeal to the King,” that defied Washington’s pragmatic solution. As first president of the Gammon Theological Seminary, Bowen stressed equal opportunity and treatment for all men, which meant higher education, not just Washington’s call for technical training and manual labor. “What is the condition for the development of the noblest type among men?” Bowen asked the crowd. “There can be but one answer to the question, namely equality of opportunity. The largest struggle of human society is to attain this concrete reality of civil justice.” He continued, “Under it, each will produce according to his ability for the good of mankind, and that good will not be a passive uniformity cast into the stereotyped mold of racial capacity…and all should be permitted to develop his endowment for the good of society within the limits of unprejudiced legislation.”33

J.W.E Bowen’s speech “An Appeal to the King,” delivered inside the Negro Building, Atlanta, Georgia on October 31, 1895

Bowen said that the education of the Negro must be equal to that of the white man, acknowledging the importance of higher education for the key to black progress. Bowen also called for equal protection under the law for black women. This new class of blacks would separate themselves from their enslaved past, ushering in a culture of black arts, educations and ownership, setting out a broader vision for the “New Negro” than the vision of Washington. Harvard historian and critic Henry Louis Gates writes that Bowen’s speech on opening day of the Negro Building leads directly to the “New Negro” and then the Harlem Renaissance.34 The appeal by Bowen to both God and man may have sounded radical to many. No wonder his Exposition speech, while important, has been buried in history, overshadowed by Washington’s “Atlanta Compromise.”

Many of the exhibits featured the work of students from 29 Southern black schools, including Spelman College, Morehouse College, Clark University, Morris Brown, Tuskegee University, and Howard University. The Negro Building also featured dozens of displays in the form of paintings, drawings, poems, photographs, inventions, sculptures and performance art from black artists, visionaries, business owners and civic leaders from fourteen states in the South. Even the content of the exhibition itself was debated, with some supporting agricultural and mechanical exhibits as the important demonstration of progress and others supporting a broader exhibition, including literature and the arts. The diversity of exhibits must have been unexpected since Washington’s speech and the official intention of the Negro Building was to encourage black progress mainly through agricultural and technical skills, not through the fine or liberal arts.35

By this time, Tuskegee boasted some 500 students and thus commanded the largest display with handmade furniture, shoes, literary pieces and photographs. The District of Columbia exhibit showcased the sculpture piece “A Negro with Chains Broken but Not Off,” by artist W. C Hill. It represented the progress, but long road ahead, for civil rights.36 Students from Hampton College displayed their achievements in geography, history, and sociology, while dental and pharmaceutical students from Tennessee showed off their own presentations. African-American artist Edmonia Lewis featured a sculpture of Charles Sumner, while poems by E.W Harper were also displayed.37

Exhibit Inside the Negro Building

African-American businesses also participated inside the Negro Building. Black owned grocers, financiers, druggists, farmers and pharmacists all used the Negro Building to promote their businesses. Although black women were barred from the all-white Woman’s Building, they held their own meetings inside the Negro Building, where women spoke out against rapes and lynchings.38

Arguably, one of the most prominent exhibits in the entire Exposition was inside the Negro Building. Nineteenth century artist, Henry O. Tanner, featured three of his paintings, “The Banjo Lesson,” “Bag-Pipe Lesson,” and “Lion’s Head.” Tanner, who was the first African-American artist to gain international recognition, depicted African-Americans far beyond the poverty and deprivation in the South. In “The Banjo Lesson,” Tanner paints a man teaching a young boy how to play the musical instrument. He “transforms the stereotype of the banjo-playing Sambo into an image of dignity, antecedents, and heritage.”39 Such imagery challenged Washington’s view that industrial education was the key to progress, but further reinforced Bowen’s call for cultural advancement.

In Alain Locke’s essay, The New Negro, he argues for “releasing our talented group from the arid field of controversy and debate... will lead to the productive fields of creative expression.40 Although many of the exhibits in the Negro Building were presented using white artistic tastes of the time, black art was clearly emerging. This creative expression of African American arts and culture began to form collectively, for the first time inside the Negro Building.

It was only later that Washington adopted the role of “image maker” for the growing “New Negro” movement, targeting white and black audiences alike, with his speeches in both the United States and abroad.41 But it was Bowen’s opening speech and the black counterpublic that emerged in the events in and surrounding the Negro Building that spawned the “New Negro,” and the debates that continued through the long struggle for civil rights.

THE CONFERENCES

After Bowen’s opening speech, significant conferences met inside the Negro Building, where sharing of knowledge, debates, organizational efforts for education, business and the professions began.42 These include, among many, the Negro Physicians and Surgeons Congress, which is known today as the National Medical Association. As the country’s largest and oldest African-American medical organization, the NMA had its beginning at the Cotton States Exposition where black delegates met in response to their denied entry in the American Medical Association. By 1905, the organization boasted 50 members. Today, the NMA has more than 50,000 members of the medical professions.

Henry Ossawa Tanner’s “The Banjo Lesson,” was displayed inside the Negro Building

Other important counter-movements inside the Negro Building included a three-day Africa Conference, organized by Bowen, the Colored YMCA Congress, the National Afro-American Press Meeting, and the Educators of Colored Youth. An African-American woman’s conference also took place in the Negro Building.

THE LEGACY

It was here at the Negro Building, in 1895, in Atlanta, in Piedmont Park, at the Cotton States and International Exposition that the legitimate vision for the New South was born, and the long struggle for civil rights began. Without the separate Negro Building, the Cotton States and International Exposition would not have received federal funds and would have left Atlanta struggling to become the capital of the South. More important, it marked the first time a global audience witnessed the achievements and challenges of African-Americans since their Emancipation and initiated the idea of the New Negro and the emerging dream of full civil rights. And it was the Negro Building – its exhibitions, conferences, speeches and the building itself – that initiated the long debates about civil rights, public life and race in America.

It would be more than a half-century until the struggle for civil rights would finally overturn “separate but equal” in the Supreme Court’s Brown v. the Board of Education. And it would take more than another decade for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 to finally dismantle Jim Crow and usher in a new era and a legitimate New South. But in 1895, African-Americans gathered in Atlanta for their long walk to freedom at the Negro Building during the Cotton States and International Exposition. The time is now for the Negro Building to be commemorated and become an important part of not just Atlanta, but American history.